Image source: Department of Defence

“What happened here in the Northern Rivers [in 2022] with Lismore as the epicentre has to be recognised as one of the worst disasters the nation has ever seen,” says Lismore City Councillor Elly Bird. The scale of the floods was immense: Australia’s “biggest natural disaster since Cyclone Tracy in 1974, the second-costliest event in the world for insurers in 2022, and the most expensive disaster in Australian history.”

With all the devastation and disruption, what lessons do the rest of Australia need to learn from the Lismore and Northern Rivers floods? What is it we need to know so we can start planning now for what will inevitably be a future of increasing and cascading natural disasters?

The February 2022 Lismore flood was classified as a 1 in a 1000-year flood, yet it was followed in March by a “1 in 100” year flood. That’s not supposed to happen, yet it did: “Because of the damage already ‘baked in’ to our Earth’s climate, extreme weather events are already intensifying, and are projected to get worse.”

Although only five people died in the 2022 Lismore flooding (four in February and one in March), a massive 31,000 people were displaced and more than 3,000 businesses were disrupted affecting more than 18,000 jobs, including almost 1,000 agricultural jobs. In fact, heatwaves are the deadliest natural disasters in Australia, but floods are our most destructive.

The floods affected about 11,000 homes in the Northern Rivers region, of which more than 4,000 – mostly in Lismore – were deemed uninhabitable. Advance warning of the weather and scope of flooding and communications during the disaster were inadequate. The centre of the Lismore commercial district was completely inundated. Emergency services were quickly overwhelmed with requests for assistance. People were rescued from rooftops, many “by a small flotilla of volunteers in boats, kayaks and canoes.” The destruction was “so intense it looked like a war zone”. Post-disaster financial assistance was slow and often insufficient. Even supermarket shelves remained empty for months afterwards, extending the trauma. A parliamentary inquiry “found that the NSW Government failed to comprehend the scale of the floods … when it was one of the greatest natural disasters in generations.”

Image: ACE Community Colleges building in Lismore CBD after the floods

It wasn’t just Lismore. Much of southeastern Queensland and northeastern NSW was affected, including the NSW LGAs of Ballina, Byron, Clarence Valley, Kyogle, Richmond Valley and Tweed, as well as Hawkesbury in northwest Sydney.

But Lismore remains the symbol of the flooding because of the utter devastation, loss of housing and the continuing despair and trauma experienced by residents.

Here are eight lessons the rest of us in Australia should learn from the Lismore experience to help us prepare for climate-connected disasters:

1. Natural disasters – fuelled by climate change – will continue to cascade, overlapping and growing in frequency. “Disaster is no longer unprecedented,” says Lismore MP Janelle Saffin. The 2022 floods were just the continuation of a series of natural disasters that affected Lismore: bushfires, drought, the mice plague, COVID-19 and then the “mega-flood of 2022”.

2. The climate crisis worsens inequality and inequality worsens the climate crisis. Many Lismore residents in low-lying flood-prone areas were already vulnerable and living in less resilient accommodation, with fewer resources and networks available for post-flood support. “Older people, people with disabilities and those who were pregnant” faced life-threatening circumstances, and often received no assistance. “Climate change impacts people experiencing financial and social disadvantage first, worst and longest because they have fewer resources to cope, adapt and recover, and because they already experience barriers to services and support,” says ACOSS. In a future “net zero” world: “People with the least will still be worse off if the transition is not fair and inclusive…. because those on low incomes pay disproportionately more of their incomes on essentials.” Inequality and disaster vulnerability are two sides of the same coin: “Disasters disproportionately impact the poorest and most at risk people.”

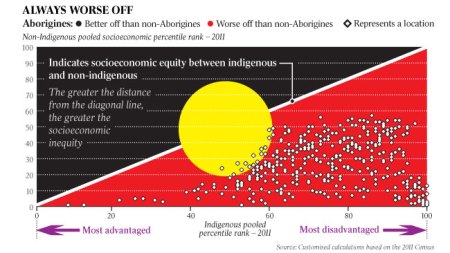

3. Indigenous Australians contribute least to climate change but experience its worst impacts. As of August 2022, six months after the disaster, 1,296 people were still homeless in the northern NSW region, 500 of whom were First Nations people (39% of the total). Indigenous Australians were thus seven times more likely to have become homeless because of the floods, as they constituted only 5.6% of Lismore LGA residents (2021 census). One Indigenous community, with almost 100 people on Cabbage Tree Island in the Richmond River (in Ballina Shire), was totally destroyed by the floods. It will not be rebuilt due to “an unacceptably high risk of exposure to future flooding events and a real risk to human life”. “Mother Nature has spoken. Cabbo is no longer safe for our mob to live there,” said community leader Lenkunyar Roberts. It’s not just east coast flooding: country town and remote Indigenous communities are particularly at risk when facing hotter and drier conditions, resulting in pressures on the supply and quality of water, food and traditional food sources. There is widespread consensus that climate change policies need to “recognise that the adaptation strategy for Indigenous communities are likely to be different to those for non-Indigenous communities”, with work “undertaken to develop culturally-appropriate strategies for this type of settlement”.

4. Housing unaffordability and the climate crisis are linked. Even prior to the 2022 floods, the Lismore region had many “rough sleepers”, several with complex social and emotional needs (and many of them Indigenous). After the floods, the situation turned catastrophic; the destruction of so many homes exacerbated a housing crisis that has not yet abated. While much of the recent national housing attention is focused on capital cities like Sydney, housing costs in regional areas – far from the eyes of Sydney or Canberra policy makers – have soared. An NCOSS submission states: “People are living in unsafe environments because there’s nowhere else to go. There’s massive overcrowding and First Nations communities are really struggling. Many of the homelessness workers [themselves] are homeless. People are living in the mouldy rotting husks of their houses…. Homeless women who were at the end of the queue and who couldn’t list an address in a flood impacted area are not even in the queue anymore.” MP Jannelle Saffin uses the term “internally displaced people, which is usually in the context of refugees from a war zone or major overseas disaster, but that’s what’s happened to us.”

5. Natural disasters produce an increasing mental health burden. Research shows “mental health effects on traumatised communities can peak up to 6 months after the event and again at 12 months, marking the anniversary.” There is widespread lack of awareness about the “long tail” of a disaster. “A common theme was hearing that mental health support and other services … were removed too soon following disaster – whether this was the availability of social workers and counselling services.” Outreach is also essential, as some people – such as those in Lismore still suffering from “collective trauma” – will never reach out for support.

6. Connected communities matter in disasters. Building social capital – informal support and access to information systems; and social infrastructure – community centres, showgrounds, universities, schools and libraries; are both essential responses to climate change adaptation. Socially excluded individuals have less social capital with which to cope, so increasing social connectedness means building robust social networks that can better coordinate recovery. In February 2022 Southern Cross University’s Lismore campus functioned as post-disaster model local social infrastructure. It transformed into “the primary emergency evacuation centre” with more than 1000 people, a home for police and community services, food distribution channels, re-located schools and more than 500 ADF personnel.

7. Climate change is creating an insurability crisis with worsening extreme weather and sky-rocketing premiums. The Insurance Council of Australia says almost 230,000 homes face a 1-in-20 chance of being hit by floods in any given year. It warns of a growing number of residents in “disaster-prone areas not buying insurance because of the higher premiums”, with flooding accounting for more than 54% insurance industry losses in the past five years. The Climate Council says by 2030, 4% of Australian properties will be “high risk” and uninsurable and another 9% of properties will reach “medium risk”.

8. Regional and rural Australia will disproportionately suffer the most from climate-related disasters. They are more exposed to natural hazards and up to twice as likely to be affected by flooding and bushfires.Country towns – already at risk because of economic restructuring and demographic change – may find climate change compounds difficulties. “This has implications both for our understanding and interpretation of the impacts of climate change, and in the development of policy responses.”

Posted by donperlgut

Posted by donperlgut

(photo above: David Gulpilil in

(photo above: David Gulpilil in