(Image above: High density apartment buildings in St Leonards, Sydney)

(Originally ublished at https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/sustainability-new-south-wales-apartment-living-has-long-don-perlgut-pggtc/ on November 3, 2023)

Two of Australia’s greatest challenges are dealing with housing supply and affordability and a growing crisis of climate change, including increasing natural disasters fuelled by a changing climate. Australian Governments take both issues seriously, but not necessarily together. That’s a mistake, one we will pay for decades to come if we do not get it right.

New South Wales and Sydney lead Australia in the housing unaffordability crisis – the lowest in decades. Sydney’s median property price sits at “13.3 times the median income; 35.3% of renters are in housing stress, ranked the sixth-least affordable city” in the world, ahead of even New York and London. Sydney’s chronic housing unaffordability crisis threatens “the future potential of Sydney” at a cost of “talent, innovation and productivity.” The impact falls most heavily on people who are disadvantaged and even moderate income: “more households are in severe housing stress than at any other time in our history.”

In response, “the rubber is finally hitting the road” as the NSW Government promises to prioritise housing development to “turbocharge density,” reports The Sydney Morning Herald. The goal is to increase stock, curtail sprawl and shift “housing growth eastward toward established transport infrastructure”. Priority density locations identified so far include Crows Nest, Bankstown, Kellyville, Bella Vista, Sydenham, Waterloo, Burwood and The Bays precinct. There will be more.

All logical, appropriate and necessary.

But not sufficient. Sydney’s housing development and expansion strategy needs to be connected to sustainability planning, so that the upcoming public and private investment in new housing reinforces, complements and supports environmental sustainability and energy conservation, as well as social cohesion and resilience in the face of anticipated natural disasters such as storms and heatwaves. This means providing well-designed social infrastructure – parks, open spaces, greenery, community centres, cultural facilities, diversified shopping, educational institutions, other community services including places of worship, and informal gathering spots that make a city a proper city that works for people.

Most Sydney councils attempt to address these issues but are subject to density and planning over-rides by the state government. That means that the integration of sustainability and community infrastructure could get lost in the rush to house our expanding population.

Let’s take three sustainability examples: water conservation, solar power and apartment design. Water meters: Only in 2014 did newly constructed apartment buildings in New South Wales require individual unit meters. As a result, in most pre-2014 buildings all apartments receive the same water bill as their neighbours (the total divided by the number of units), irrespective of how much water they use. Thus, the motivation for water conservation in these buildings (including my own, in North Sydney) is severely curtailed. Even if you try to save water, your bill won’t tell you if you did. Sydney Water tells me the estimate for installing individual meters in older buildings will be well more than $1,200 unit, and many buildings will find it impossible to do so. As a result, very few do.

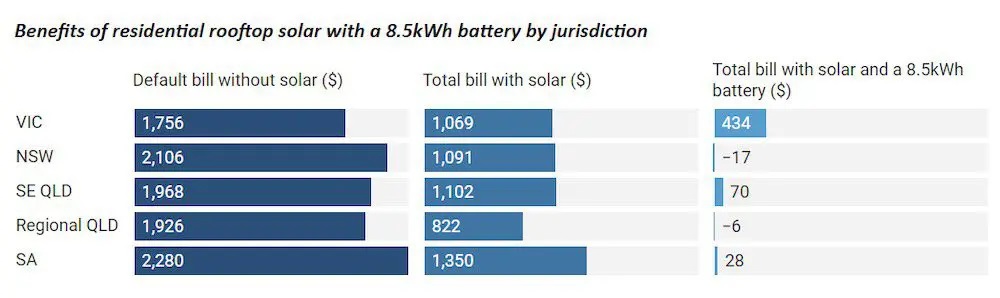

Perhaps even more powerful is that we need to plan for rooftop solar, which experts call “the cheapest delivered electricity in the world”; it can halve the cost of electricity in NSW. But apartment buildings don’t have nearly as much rooftop as houses do. And even when they do, there are challenges to reticulate solar electricity to all the units in buildings that do not already have built-in solar; only a few suppliers specialise in this.

(Chart above: Financial benefits of rooftop solar; source: https://reneweconomy.com.au/rooftop-solar-saves-money-and-batteries-can-wipe-out-bills-labor-pushes-household-savings/)

Thanks to my local council – North Sydney, running a Future-proofing Apartments Program – which quickly analysed our apartment building’s roof (see photo below sent to me via email) and identified how our flat roof was suitable for solar. There are some notable examples of existing “smart green” apartment buildings, but they tend to be prestige buildings with motivated owners committed to – and able to afford – required retrofitting.

(Image above: Apartment building rooftops: courtesy of North Sydney Council)

Finally, there is apartment design. All Sydney has abundant sun and much of eastern Sydney is blessed with cooling summer ocean breezes. Western Sydney, however, faces major heat challenges, which have already reached crisis proportions (which I will discuss in a separate article). Apartments need to be carefully planned to maximise passive design attributes: is there natural and cross ventilation that quickly cools an apartment; are there private places to dry clothes on balconies; are external windows and doors oriented to maximise northerly winter sun and eave overhangs to protect from the worst summer and western sun?

This is our challenge: to relieve Sydney’s housing crisis while placing energy conservation and climate resilience high on the priority list for our communities and the tens of thousands of high-density new units to be built in coming years; to support local government sustainability efforts such as those in City of Sydney; and to project an agreed vision for Sydney that is affordable, liveable and sustainable.

Posted by donperlgut

Posted by donperlgut